Farmer ambivalence when it comes to new technologies

Farmer ambivalence when it comes to new technologies

- August 29, 2022

- UNSW

- Blog

- No Comments

To adopt or not to adopt

Research only translates to commercialisation when it is practically driven. In 2017 when a group of researchers from CSIRO and the University of Western Australia tried to predict farmer uptake of new agricultural practices (including products and technologies), they focused on researcher design rather than farmer uptake (Figure 1). Researchers need to have a greater understanding of on-farm systems in the context of practice. Only then can they prepare and scale up (and out) new farming practices.

The figure below shows 22 variables that the researchers noted. These variables could be used to predict the peak adoption level (What are the chances?, To what extent?) and time to peak adoption (How long will it take?).

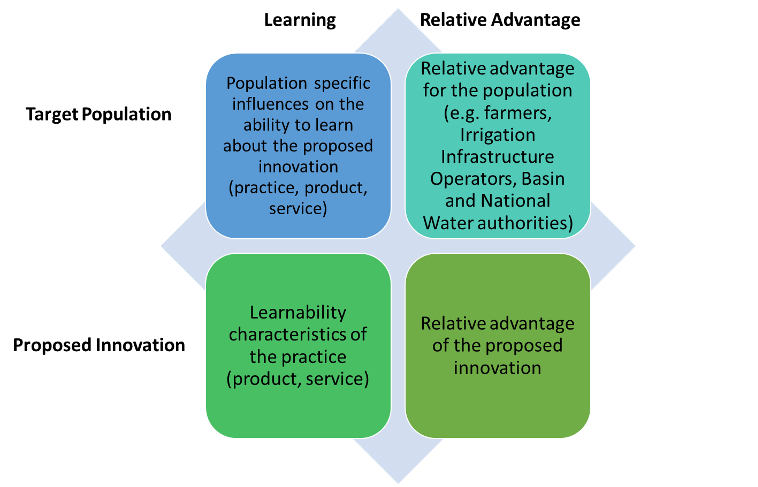

Two overarching factors influence the adoption process: the relative advantage, and the effectiveness of the process put in place to learn about the practice. In Figure 2 this is represented in the lower rectangles on ‘learnability characteristics of the practice’ and the ‘relative advantage of the practice’.

In this blog, we focus on the peak adoption level that appears to be driven by clear communication by the product developers of the relative advantage of the product/service offered. That relative advantage is connected to the concept of ‘learnability of the practice’ that is being promoted. It appears that the amount of farmers or advisors are ready to embrace and uptake a new product or service and time to peak adoption are connected to complexity of the practice, ease of trialing, and capability of framers to gain awareness through local observation. Researcher awareness of the ‘characteristics’ of the target population, their networks and inherent skills are also essential to foster adoption.

In COALA, we paid attention to all of the above factors by segmenting the target population into three groups with common goals (sustainable land use) but differentiated needs. One of our identified segments is the ‘farmers, small and large scale agribusinesses” segment. They have information needs about irrigation volumes and the spatial and temporal distribution of some crop characteristics (i.e. crop vigour) over the growing season for each of their paddocks; and on crop canopy development, which is the result of all agronomic practices. Once they have that kind of information they can use it for better management of crop inputs. Furthermore, spatial information provided by satellite Earth Observation (EO) is an ideal complement to the in-situ measurements often available at the farm level, such as soil moisture sensors and agrometeorological stations. Adopting products and services that embrace the synergy of these technologies —as offered by the COALA project— can increase farmer’ revenue through yield improvements.

The “River Basin Authorities” segment needs information related to improving water resource management to match water allocations with the actual crop water requirements to match the constraints of the basin plan.

The ‘segment’ of Irrigation Infrastructure Operators (IIO) and Water Managers must comply with contractual and environmental constraints and limitations derived from water resource availability (arising from the Basin plan). Products such as maps of crop water requirements, maps of irrigated areas, maps of crop vigour and other products derived from EO-data processing are helpful to this end. And, these maps can help water manages in their day-to-day tasks if they are aggregated over different temporal scales (weekly, monthly, etc.) and land management units (field, farm, district, etc.). Furthermore, water managers can aggregate this information at the irrigation district level to adequately plan for water allocation according to water availability and the basin plan.

COALA’s focus is on transfer technology and services that have proven to work in other countries. So, paying attention to population-specific influences on the ability to learn about the practice and the ‘learn-ability characteristics of the practice’ (see Figure 1) are paramount. That is why one of the first stages of our project focused on understanding users’ interests and needs. We did that through surveys and interviews with representatives from the target population to learn about their networking, skills, awareness of proposed practices, profit orientation, and readiness for risk-taking.

From the interviews, we listened to the voices of the prospective users. For instance, from an irrigator, we learned that “This industry has a great knowledge-sharing attitude, where we have field days in stuff. And so, new techniques expand regionally, from the experience of individuals, I think, more so than the other way round…and you need to have a competitive industry, where your suppliers are also, constantly, trying to produce you a better product, so they can sell their product to you… So, I think any new technology, the best way to get it out there is through a network that’s already established”.

We used that information to design tailored products (Figure 4), to prepare the COALA business plan, the commercialisation road map of the proposed COALA solutions, and to explore options to translate research outputs into commercially viable practice. From work undertaken for the COALA project, the consortium partners understand that understanding end products, doing market analysis, competition analysis, and pitching the value proposition of each of the bundles of services and products (figure below) that COALA will offer once the research is completed in June 2023 is essential (as said by CSIRO and UWA researchers) to encourage adoption.

Like the research of CSIRO and the UWA mentioned at the beginning of this blog, our interaction with the prospective users has shown that farmers and advisors favour ease and convenience of the practice. This preference is exemplified in this statement of an interviewee we condcuted in the initial stage of the COALA project: ‘..,there has been a lot of farmers that have attempted at adopting these types of technologies, or had a go at it, found not much use for it, and probably have it there in the background but don’t use it regularly is probably … for a farmer to adopt something, they need it to happen automatically.”

Farmers, advisors and water irrigation authorities are exposed to myriads of products and services with the potential to be translated into practice. The extent of that occurring depends in part on research and funding for innovation directed to products and services that are relevant to agriculture. These products and services should be simple enough to be readily used and understood by practitioners who may not be specialists in specific technologies (e.g. Earth Observation).

Graciela Metternicht and Bonnie Teece, UNSW.

Reference: Kuehne, G., Llewellyn, R., Pannell, D.J., Wilkinson, R., Dolling, P., Ouzman, J. and Ewing, M., 2017. Predicting farmer uptake of new agricultural practices: A tool for research, extension and policy. Agricultural systems, 156, pp.115-125.